A decade-long national study conducted by the University of Western Sydney found that nearly half of Australians describe themselves as having anti-Muslim attitudes.

These findings could hardly come as a surprise to anyone familiar with the sheer amount of blatant Islamophobia that is reported through the Islamophobia Register Australia.

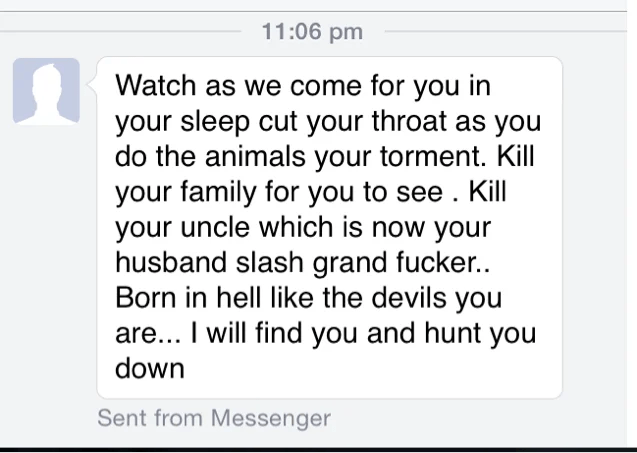

I myself have struggled tremendously, both physically and mentally, after being singled out by the Australian Defence League, and finding myself on the receiving end of death threats and near-constant online bile.

This is part and parcel of being a visible Muslim in Australia today, who quickly become the target of social media vitriol, verbal abuse and physical assaults every time someone or something even remotely associated with Muslims or Islam is thrust involuntarily into the media spotlight.

The word “Islamophobia” was coined because there was a new reality that needed naming – namely, anti-Muslim prejudice. Just to be clear, this is not a matter of theological debate and disagreement, much less criticism of Islamic teachings and practices. This is about bigotry, discrimination, abuse and, I will argue, racism.

Is Islam an ethno-religion?

The category of an ethno-religious group was created to cope with anti- Semitism as a special form of racism. This was the right move, in my view. This grouping was created because this particular group of vulnerable people went through a process of “racialisation” over time.

But it is time that we understood the ethnicised and racialised nature of Islam in Western countries, and recognise Islamophobia as a form of racism akin to anti-Semitism.

What exactly is racialisation? It is defined as the process by which groups are categorised and accorded certain phenotypic features that stems from their way of living. Ultimately, racialisation results in essentialism – it reduces people to one aspect of their identity and thereby presents a homogeneous, undifferentiated, and static view of an ethno-religious community.

Randa Abdel-Fattah, who has explored at length the various forms Islamophobia takes in countries like Australia, challenges the claim that Muslims cannot be the victims of racism because they are not a race. This claim, she argues, is based on an impoverished understanding of the history of race, racial formation and racism. She argues that the body-fixated theory that sustains a demarcation between race and religion ignores the enormous scholarship carried out that demonstrates the falsity of claiming that religious affiliations are never to do with the body, and that “race” is only to do with the body. She argues:

“that racial marking and racialisation do not depend on so-called biological attributes. Essentialising people on the basis of their outward appearance – whether it be skin colour, facial features, a headscarf, beard, an accent – is precisely how the process of racialisation works.”

While it is certainly true that being a Muslim is voluntary and not a biological trait per se – in the way that “African American” or “South Asian” or “European” is – as Nasar Meer and Tariq Modood point out, originally, neither was being “Jewish.” They argue that it was took a long, non-linear process of racialisation to turn an ethno-religious group into a race.

I am mindful that some may be insulted by any comparison of Islamophobia with anti-Semitism, on the grounds of the exceptionalism of the history of Jewish hatred in the West. I am, of course, not seeking to downplay the long history of persecution suffered by the Jewish communities.

The real issue, however, is the apparent double-standard, the anomalies and contradictions that are embedded in anti-discrimination legislation, which lead to unjust but legally compliant decisions whereby, for a complaint against comparable offences when religion is not a protected attribute, a Jewish person can obtain reparation while a Muslim cannot.

A prime example of such a double-standard is the 2002 case of a Muslim prisoner in New South Wales who filed a case when he was denied his request for Halal food in a private prison, knowing full well that his Jewish inmate obtained his Kosher meal when requested. The court stated that, since Halal food is of a religious element and religion is not covered under the New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Act (1977), therefore the case should be dismissed.

Such inconsistencies in the application of the law – whereby a religious dietary requirement was obtained by one religious group but denied to another – are highly problematic and demand some redress.

But, as Mariam Farida rightly argues, even if Muslims were considered an ethno-religious group, they may not be protected from religious discrimination under the law. Making reference to specific cases, she concludes that even if a party belonged to an acknowledged ethno-religious group, the court may only consider it a breach if the vilification was both on the grounds of ethnicity and religion, and not purely based on religion alone.

We thus need to consider whether having Islam categorised as an ethno-religion would actually achieve the intendedobjective.

The Racial Discrimination Act and religion

This leads inexorably to the question of whether the Racial Discrimination Act be amended so as to extend to religious vilification. Quite apart from the obvious body of opposition to such a proposition, I suspect that the likes of Andrew Bolt would have a hernia. He’d have to acquaint himself quite intimately with what it means to write something in “good faith”!

I acknowledge that there is a deep-seated resistance to include religion among the grounds covered by anti-discrimination laws. Interestingly, despite the fact that some Christian groups oppose religious vilification laws, the Australian Christian Lobby in its 2012 submission in relation to the Consolidation of Commonwealth Anti-Discrimination Laws proposed that religion be a protected attribute against discrimination, in order to remedy a substantial omission in the Commonwealth legislation.

In Australia, the states that cover religious discrimination in their legislations are Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, the ACT and the Northern Territory. I note that New South Wales contains Australia’s largest Muslim population, and yet they are not protected from religious vilification. Interestingly, the New South Wales Anti-Discrimination Act (1977) was amended in 1994 to add a reference to “ethno-religious.” The then NSW Attorney-General, John Hannaford, explained that “the effect of the amendment is to clarify that ethno-religious groups, such as Jewish people, Muslims and Sikhs, have access to the racial vilification and discrimination provisions of the Act.” The stated intention was, in fact, to cover Australian Muslims – but this never materialised.

One of the objections often raised against making religion a protected attribute under the Racial Discrimination Act is that religion is deemed strictly personal and tends to be chosen. This is true. Though it is important to point out that in circumstances where a person finds herself born to a Muslim family, with Muslim stereotypes and characteristics, then it could be argued that it is not a matter of choice anymore.

When examining this objection from a purely practical perspective, one does not choose the name they are given or the family into which they are born. One doesn’t choose to be named Mohamed Abdulla, for example. Yet, even if there were no other identifying features, this name alone is enough to identify a man as being a Muslim and therefore make him prone to being the subject of religiously motivated abuse.

Furthermore, researchers have made the point that one does not choose to be born a Muslim in a society where identifying as Muslim makes you the subject of suspicion and interrogation. If choice is the factor that precludes a Muslim from being seen as a victim of racism, then isn’t the logical conclusion to be drawn that such a choice is a bad one? If a Muslim is the victim of a hate crime but cannot seek legal recourse because the attribute that attracted the abuse is “chosen,” isn’t the clear message that concealing this choice – that is, being less Muslim – would go a long way towards preventing the abuse?

Sure, I’d cop far less abuse if I chose not to wear a hijab – but why should I be forced to make such a choice? One cannot help but feel that the victim is here being blamed or made to feel as though they are inviting the abuse. This line of moral and legal reasoning is deeply flawed, and is comparable to someone blaming a woman’s dress sense for her being the victim of sexual harassment.

The impact of Islamophobia

Where religious groups or individual believers are subject to vilification, it can have deeply hurtful effects and create considerable fear within religious communities. It also feeds into a vicious cycle. Islamophobia, if left unchecked, may serve to erect barriers to Muslim inclusion in Australia, increasing alienation, especially among young Muslims. Not only would such a situation do grave damage to our social cohesion, it would simultaneously expand the pool of recruits for future radicalisation. This factor is often ignored or overlooked.

Let me conclude by citing an article by my dear friend, Randa Abdel-Fattah:

“Do you want to know how it feels to be an Australian Muslim in the Australia of today?

“Then turn on the television, open a newspaper. There will be a feature article analysing, deconstructing, theorising about Islam and Muslims in which your fellow Australians will be offered the chance to make sense of this phenomenon called ‘the Muslim’.

“This is what it means to be an Australian Muslim today. It is to try to live against the perception that one represents a synonym for terrorism and extremism.

“It is to see the faith you embrace with such conviction defiled and defamed because acts that defy Islamic law and doctrine are still prefixed by the media with the word ‘Islamic’. It is to have the reasonable, peaceful statements of your leaders ignored and the ignorant ravings of the minority splashed across the headlines. It is to be the topic of talkback radio rant and raves.

“It is to come to accept that although atrocities are committed in the name of all religions around the world, it is Islam alone that will be judged by the actions of those who purport to be its followers. It is to refuse to lay blame for the behaviour of so-called Christians at the feet of Christ because you respect the intent of Christ’s words and actions and because you know that even those acting in his name are misguided.

“So what it means to be an Australian Muslim today is that you will often sit alone, in the silence of your hurt and fury, and wonder why it is so difficult for Islam, a religion followed by 1.5 billion people, all of whom cannot be uncivilised, unintelligent, immoral, unthinking dupes, to be treated with the same respect.”

Is it not unconscionable for some religious minority groups to be afforded legislative protections and other religious groups, who are also in desperate need of such protections, to be denied the same protections?

Mariam Veiszadeh is a lawyer, community advocate and founder of Islamophobia Register Australia. An earlier version of this article was presented to the RDA@40 Conference in Sydney, 19-20 February 2015.

Bigoted, Neo-Nazi and white supremacists groups have been trolling Mariam – on and off – for years.

Bigoted, Neo-Nazi and white supremacists groups have been trolling Mariam – on and off – for years.

After a lengthy police investigation, she was charged for using a ‘carriage service to menace, harass or cause offence’. She was sentenced in May to 180 hours community service. The sentence was considered to be groundbreaking. I have since lodged a compliant via the Australian Human Rights Commission, which is currently on foot, and have considered other legal options.

After a lengthy police investigation, she was charged for using a ‘carriage service to menace, harass or cause offence’. She was sentenced in May to 180 hours community service. The sentence was considered to be groundbreaking. I have since lodged a compliant via the Australian Human Rights Commission, which is currently on foot, and have considered other legal options.

The Police took out an AVO against her and she recently charged with using a carriage service to harass, menace and cause offence and also fined $1000. At the time, I had broken the story to a trusted journalist but I had insisted that the identify of the offender be not disclosed.

The Police took out an AVO against her and she recently charged with using a carriage service to harass, menace and cause offence and also fined $1000. At the time, I had broken the story to a trusted journalist but I had insisted that the identify of the offender be not disclosed.